The posters saying safe sex

A disease killed homosexual men in the United States in the late 70's. There was no treatment to be had. Infection meant death. It was realized early on among Norwegian homosexuals, that the "gay plague" that ravaged the United States would also come to Norway.

But in Norway the story took a different turn than in many other countries. Norwegian health authorities were responsive and initiated a collaboration with the gay organizations to prevent the spread of the virus in Norway.

Helseutvalget for homofile (The Health Committee for Gays) was established in 1983 to do preventive work.

In January of the same year, the first Norwegian AIDS patient was admitted to Rikshospitalet. He died ten months later.

I will not let a fucking nurse tell me how to fuck! Calle Almedal about the start of the epidemic. (Video subtitled in English.)

Outreach

- Helseutvalget was like the authorities' extended arm in different subcultures, says Rolf Martin Angeltvedt. He has been chairing the Helseutvalget since 2003, but has worked with HIV and AIDS since 1994.

- They visited saunas, parks and nightclubs where men met men. They allied themselves with the doorman, the cloakroom guard, the bartender and the drag queen to get them involved in the effort to spread information, he says.

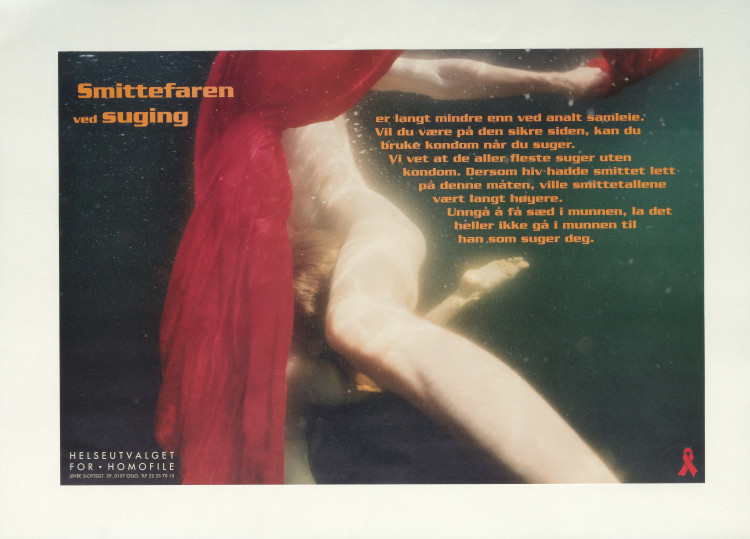

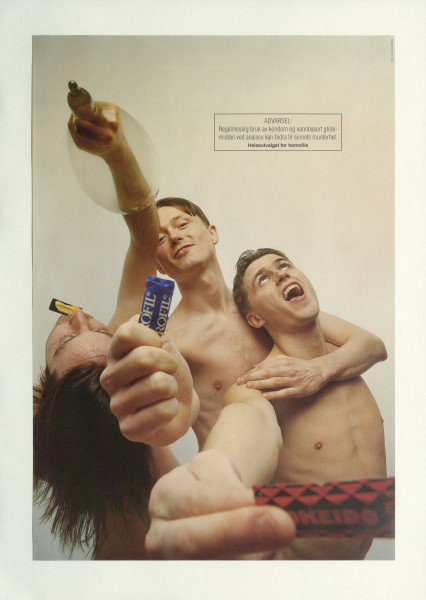

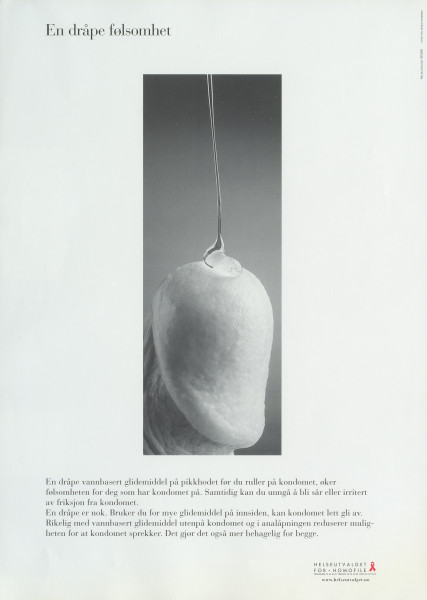

But then there were the posters. They were put up where men met, in toilets in nightclubs and in saunas. The posters had a very direct language, often with humour. Remember this was before the internet was established.

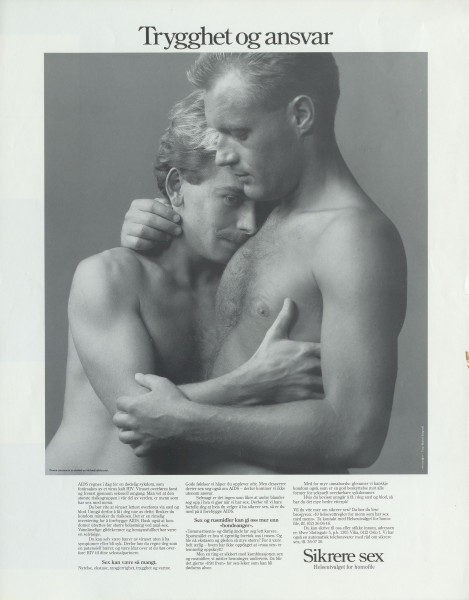

Beautiful homosexuality

Helseutvalget did not have any good experience with advertising agencies. Competent people on the gay scene did the job best.

- Arne-Harald Hanssen and photographer Finn Serck Hansen did a lot of good work in the 90s, says Angeltvedt.

Everything looked good. There were even accusations that it was all too beautiful a picture of homosexuality.

Nudity and sex

- Models were recruited from the nightclubs in Oslo. They were voluntary models, models we still use today. The message was sharp and tested on the target group, he says.

The target group was men who had sex with men in places where they met each other. The message could therefore be more direct than a poster campaign on the bus. Nudity, sex and direct language were very effective, but also created reactions.

Reactions in the Parliament

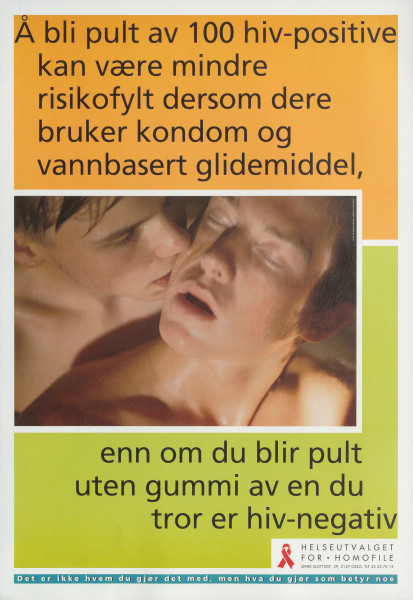

A poster said safe sex with 100 HIV-positive men is safer than unprotected sex with someone who does not know wether he is infected. This created a storm.

Parliamentarian Jon Alvheim (FrP) meant the message was too promiscuous. To say that 100 partners is ok, made both FrP and KrF react.

- This resulted in a press release from the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision which said that the money for Helseutvalget should be considered. There was full chaos, says Angeltvedt.

Internal reactions

A naked bathing man at the ready, so to speak, also provoked reactions.

But this time, from internally in the queer movement. At this time, there was great disagreement between gays and lesbians about pornography. While the ladies thought porn was both objectifying and degrading and burned porn on bonfires in the streets, the men thought porn was actually quite okay. The poster with the erected man was therefore censored by the ladies. They simply taped over the "pornographic" body part on the poster.

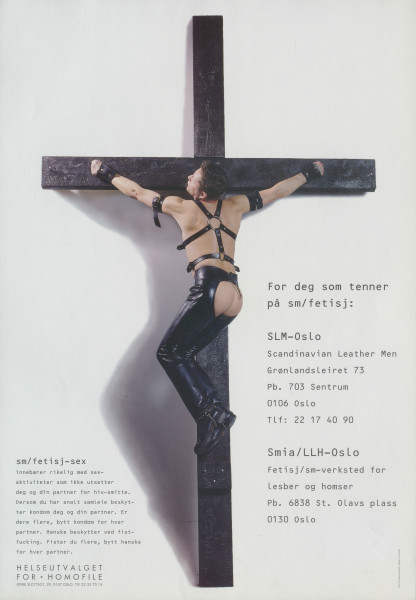

The poster with the crucified man partly dressed in leather, made the Open Church Group (ÅK) react. ÅK is part of the gay movement, but still thought this was too much and also blasphemous.

The posters were also published in Blikk, a queer magazine. But sometimes it was too much, even for the readers of the gay magazine. This resulted in several reports to the police, says Angeltvedt.

Seminar on safe sex

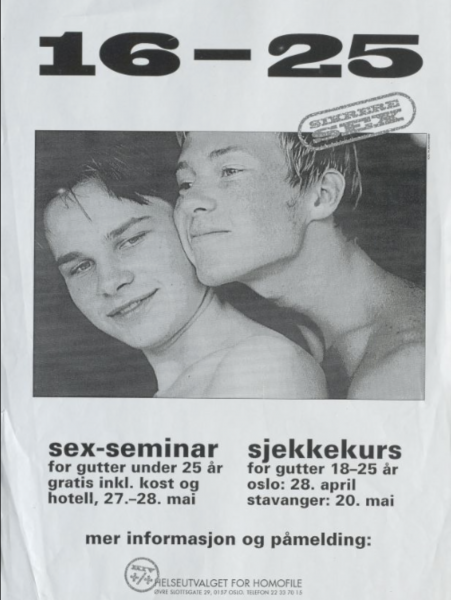

Around 1990, the Health Committee started seminars to spread knowledge about HIV. This too was presented via posters. Separate seminars were arranged for the SM group, young men, older men, patners of HIV-positive people, etc.

Weekend seminars were often at Renskau hotel in Drøbak. Departure by bus from Oslo city center. Two HIV-positive men were included as participants, but they kept their diagnosis secret as a surprise for day two. It was all about building networks. Share experiences from own lives. A new experience to many.

But not many wanted to attend the seminars. The people of Helseutvalget had to go out into the communities to invite the men, one by one. But the invitation was usually not accepted.

- To get 30 participants, we had to talk to 500 men. When the bus was about to leave, we also had to take a round in the area to find those who had not made up their mind.

- We also did not always get the right people. Those who could need it the most, he adds.

The turning point

At the start of the 90s, testing of drugs started. Angeltvedt had two HIV-positive friends participating in a study without knowing if they were given medicine or not.

- One is still alive today, the other died in 1996.

1996 was the year a working treatment was introduced. Infection no longer meant death. The focus on preventive work was weakened and the money dried up. But it turned out that the end of the 90s was when the HIV virus really started to spread in Norway. At the start of the 1990s, the infection rates were just over thirty per year. In 2008, over 200 were infected.

According to the National Institute of Public Health, the figures have gone in the right direction since 2015 due to increased testing, rapid initiation of treatment and access to preventive treatment (PrEP).